We at JuliaHub are very excited to release Dyad 2.0, the latest version of our product for modeling and simulation. At the heart of our Dyad 2.0 is an AI-first agentic workflow. This is a major release in terms of features, but perhaps even more significant in terms of philosophy. Dyad 2.0 is fundamentally about a new vision for how modeling needs to work with the future of agentic AI.

As announced recently, Dyad is a declarative domain-specific language (DSL) for engineering that unifies physics-based modeling, scientific machine learning, and agentic workflows in a single environment. In a similar vein as systems like Modelica, Amesim, or Simulink; Dyad helps engineers to express physical systems, constraints, and objectives directly in code to assemble models, run simulations, explore design spaces, and generate controller code for embedded devices.

However, we’ve used this space to reimagine what a language for modeling and simulation should be in the world of agentic AI. In fact, the resulting gains in accuracy significantly exceed what we see with tools like Claude Code, Codex, and Gemini. This gave us the impetus to run live demonstrations on user-requested modeling challenges.

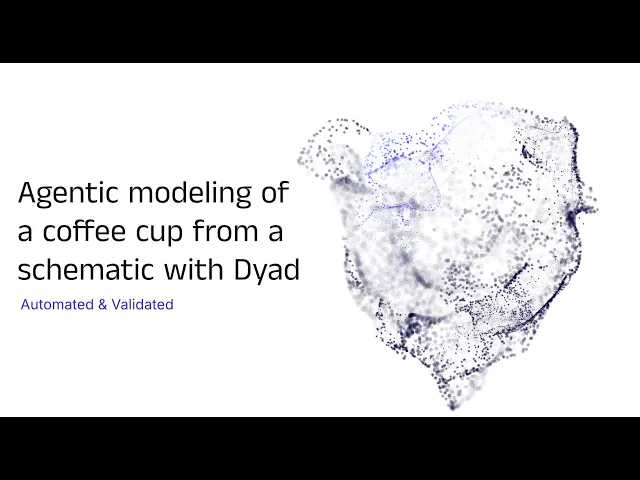

Watch how we generate a coffee cup thermal model from a schematic

This begs the question: why is Dyad as a language so much more effective for agentic AI than standard programming languages like C, Python, or Julia? To understand this, we need to look at how language design has changed over the years.

The Evolution of Computer Languages: Matching Human-Computer Interactions

Programming languages of the past were developed under the assumption that humans would create programs. As the human-computer interfaces changed, so did our languages. Early Fortran was made for punch cards: fixed numbers of columns, everything in capital letters, because that’s all that early encodings supported. These were not arbitrary choices, this was language design matching the human-computer interaction.

It looks exactly like punch cards on a computer screen for a reason

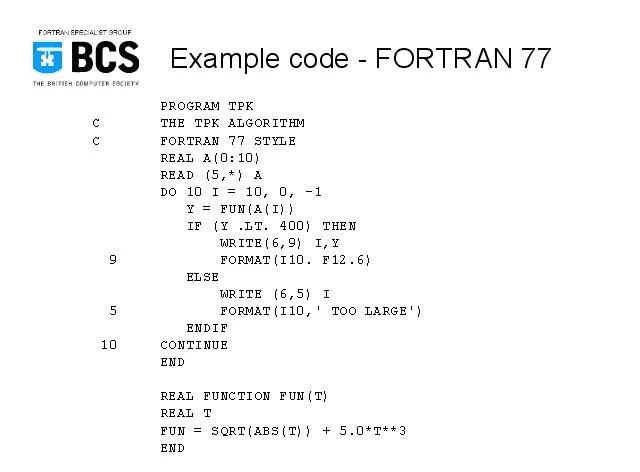

As the human-computer interface changed, so did our languages. C was created for humans working at a terminal, where { these brackets } were easy visual indicators of where clauses started and ended. These languages were co-designed with the tooling around them: style guides and syntax highlighting were created to accentuate the elements of the language to the human, and updates to the languages were made to fit them better for these designs.

A programming language made for CRT screens

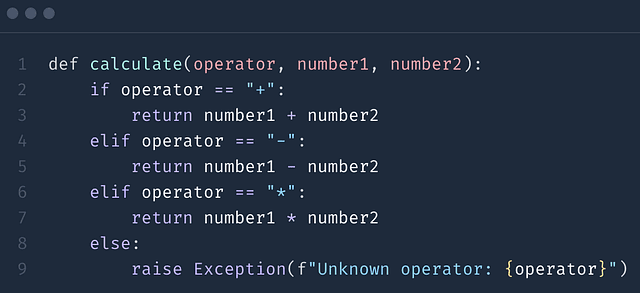

Languages continued to evolve, bringing these elements all the way forward. A major example of this is Python, which took the stance of “if indenting code is something everyone does to make code more legible, what about requiring indentation as part of the language?” Instead of relying on brackets or other delimiters, the tabbing or whitespace became how code blocks were indicated. The least number of characters to signify intent. .

Programming enters the Steve Jobs design era

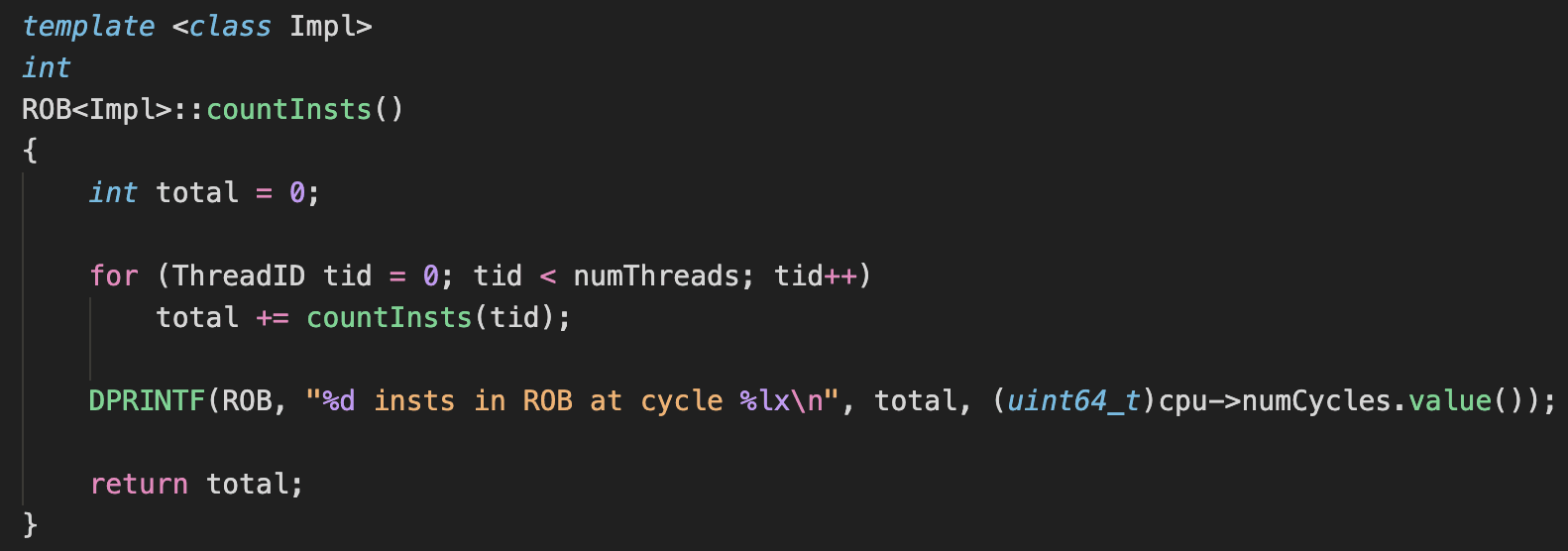

While Python may have perfected simplicity for humans to specify “what” programs need to do, future languages then improved on specifying “how”. The how of a program is equally important: just getting the job done does not mean that it’s done in a way that is fast, safe, compatible with real-time, or similar requirements. As programming continued to evolve, making use of parallelism, GPUs, embedded hardware for edge computing all began to have these additional requirements which required new programs and ultimately, new language designs. Languages like Julia and Rust began to mix in elements of complexity, like types, into the form of a high level language with simplicity, attempting to give the best of both worlds.

Boil language down to its very essence

Agentic AI is Here, And It Means We Must Develop Differently

Today, we are seeing a fundamental change driven by agentic AI. Instead of humans writing code directly, work increasingly begins with a query to an AI system, which generates code for humans to review and guide. This change in human–computer interaction forces an important question: how must our system and language designs evolve to support this new mode of work?

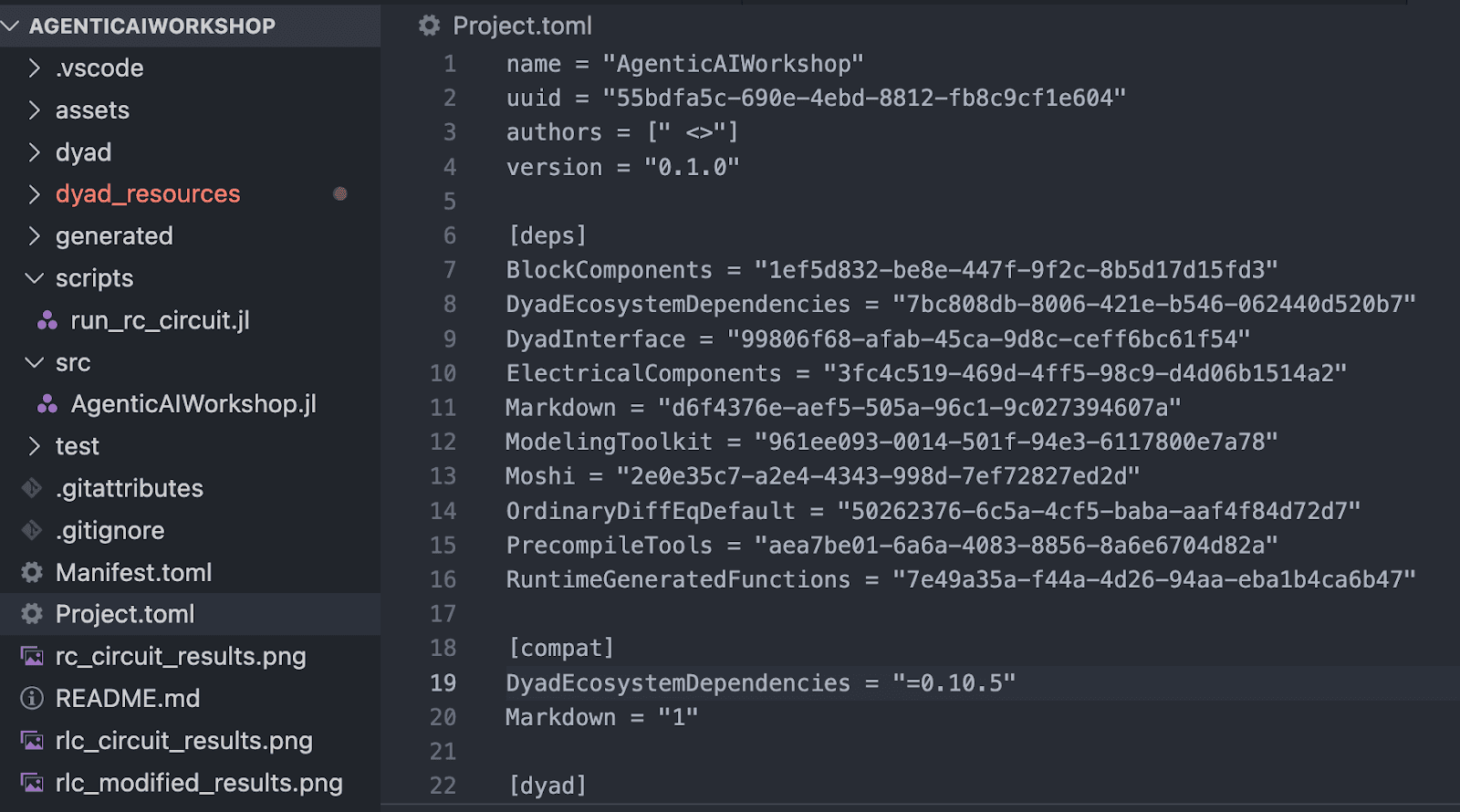

Consider a simple anecdote: when agentic AI systems like Claude Code first came out, they were not very good at adding new dependencies to Julia codebases.

Julia dependencies are declared in a Project.toml file with a machine-generated, unique identifier associated with the name of the package (to handle naming conflicts). The problem is that the agentic systems with their tendency to hallucinate unique IDs, resulted in outputs that look similar, but were not actually correct, thus breaking the environment.

The Julia package manager was then updated to validate if this package existed but the unique ID did not. It returned an error:“this package does exist, did you mean with this ID though?” showing the correct one. With that one change to the error message, it went from working ~10% of the time to >99% of the time, without a single change to the LLM.

When small changes to language design have such a large impact on the accuracy of agentic AI coding systems, we have to ask, what do we need to change about our programming languages?

UUIDs just look like random strings, and LLMs thought we wouldn’t notice!

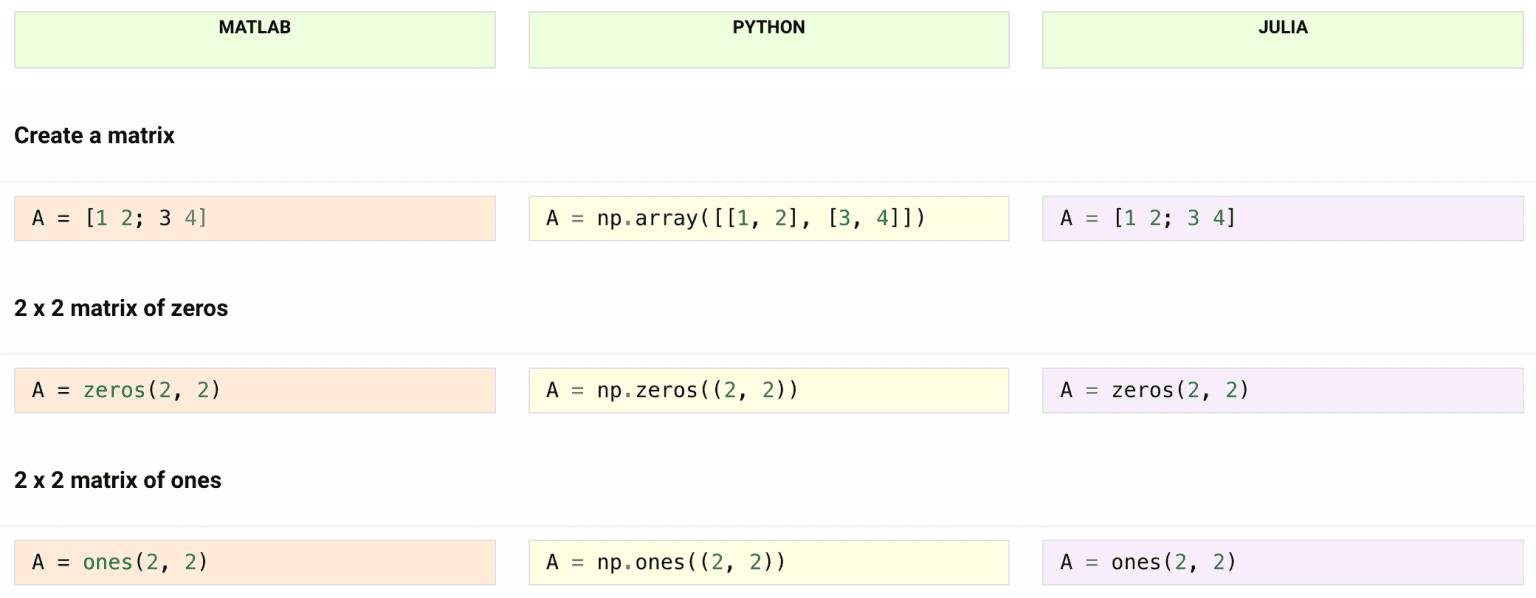

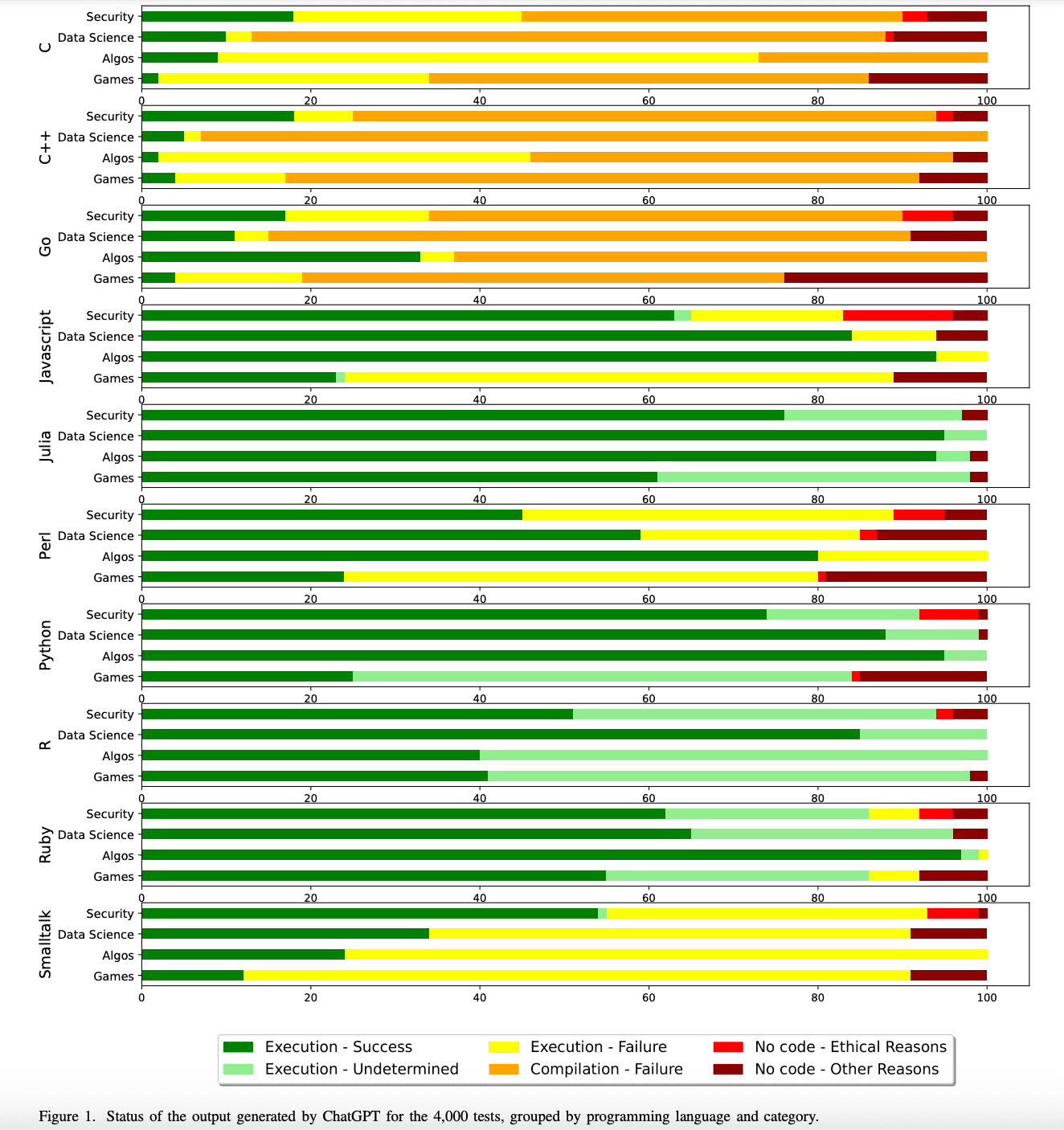

Empirical data further guides us towards the idea that some language designs are more amenable for agentic AI systems. One paper showcased that simpler high-level languages like Julia and Python which have less syntactic complexity achieve higher performance than more syntactically complex languages like C.

Languages for which LLMs generated the most successful code show the most green. Julia, Python, Ruby, Javascript all are in that category

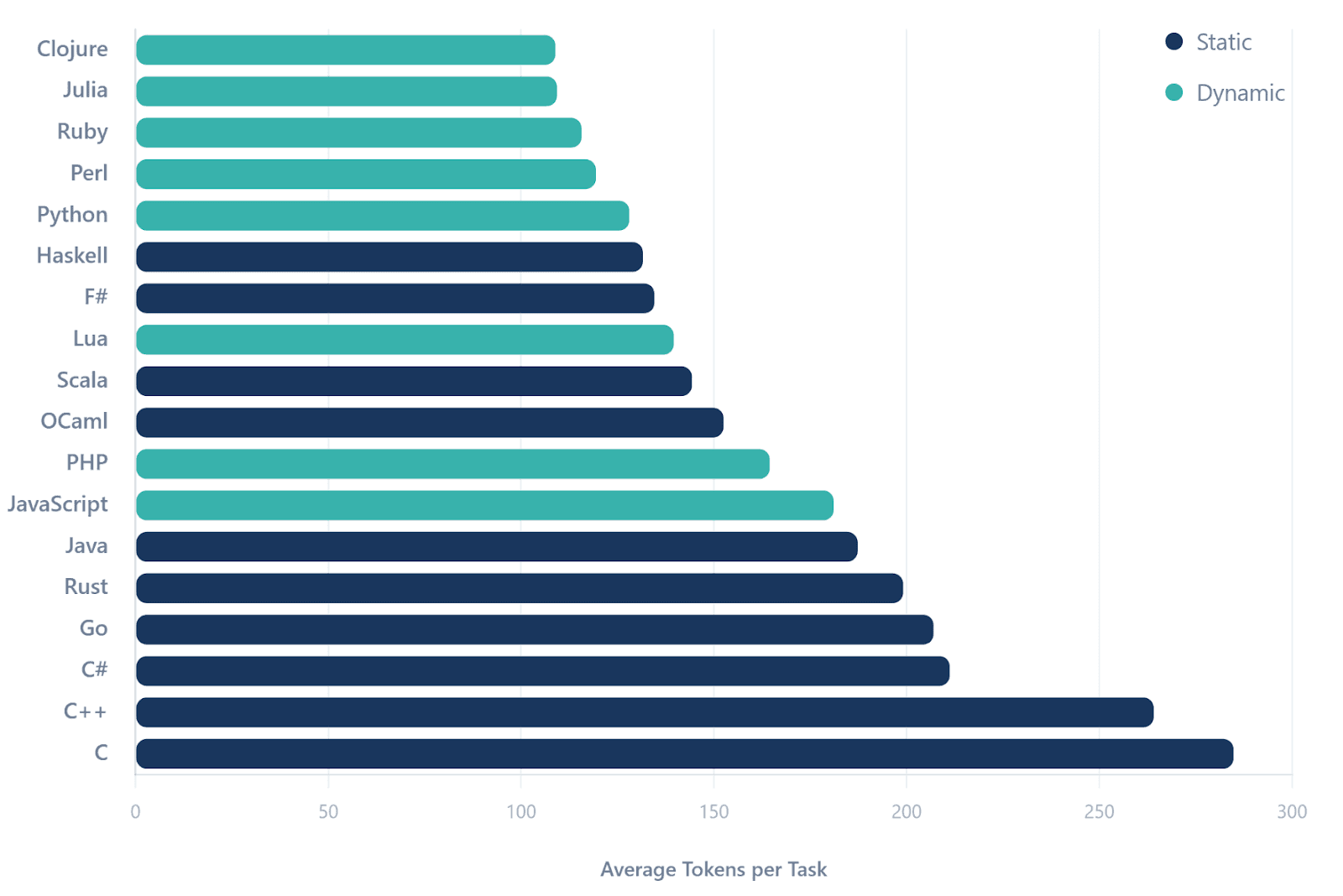

Similarly, languages like Julia and Ruby which have simpler syntax were shown in other benchmarks to be the most token-efficient.

More token-efficient languages means agentic AI systems take less work to produce accurate outputs, and the most efficient all seem to be terse dynamic languages

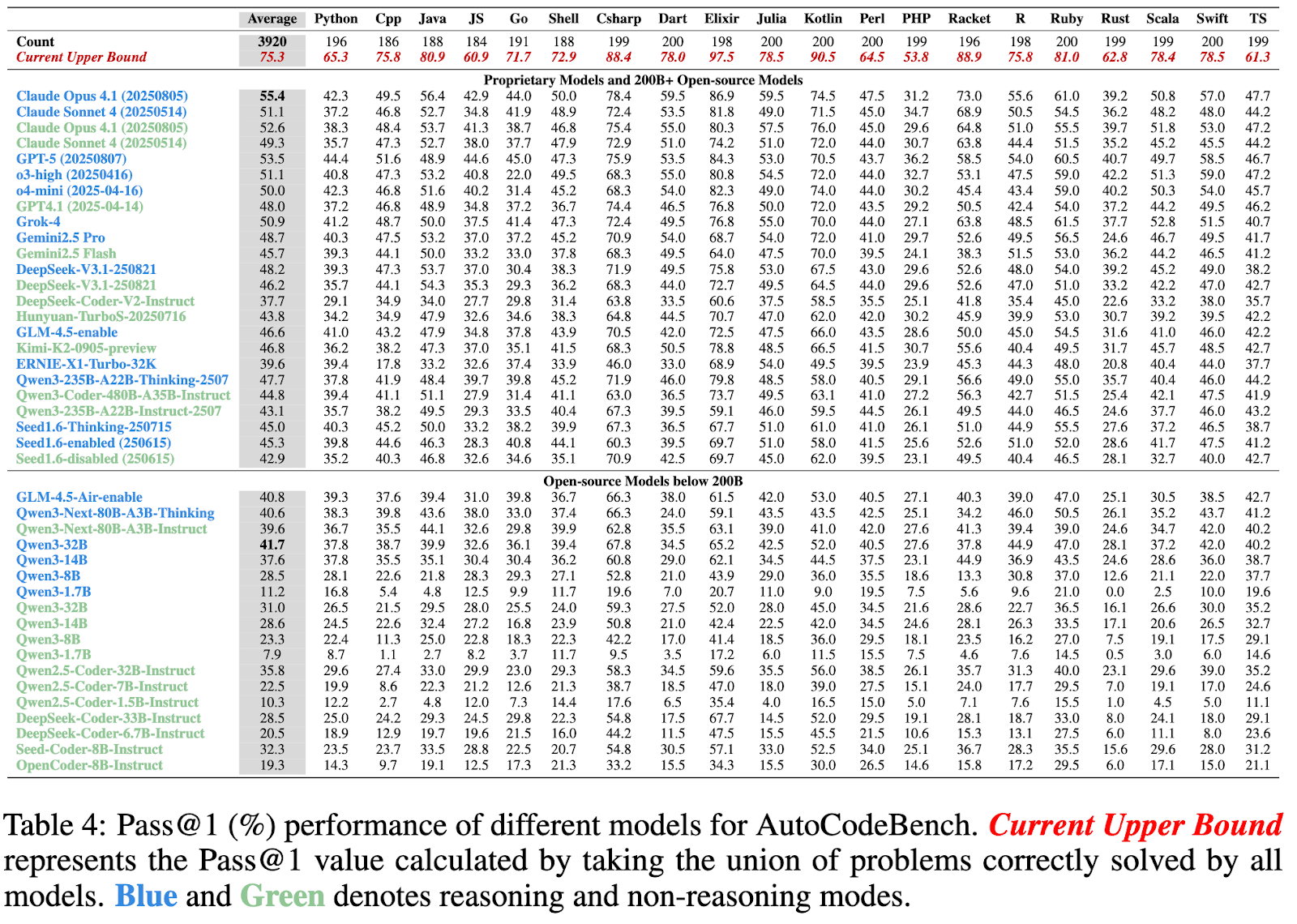

But that was the LLMs in isolation. A new autocode benchmark looked at agentic AI systems as a whole. In this setting , languages with more static information like Julia, Kotlin, Swift tended to outperform languages like Python, even though agentic systems are more heavily trained and tuned for Python..

Caption: When benchmarking with the full agentic scaffolding around, statically compiled languages like Rust and Swift start to do really well

There is a trend:

Simpler syntax makes LLMs more accurate + better static compiler feedback gives better agentic feedback => higher agentic AI accuracy

This begs the question, what if we designed a language for LLMs and an agentic AI system based on these principles?

Dyad 2.0: Built for LLM Performance and Accuracy

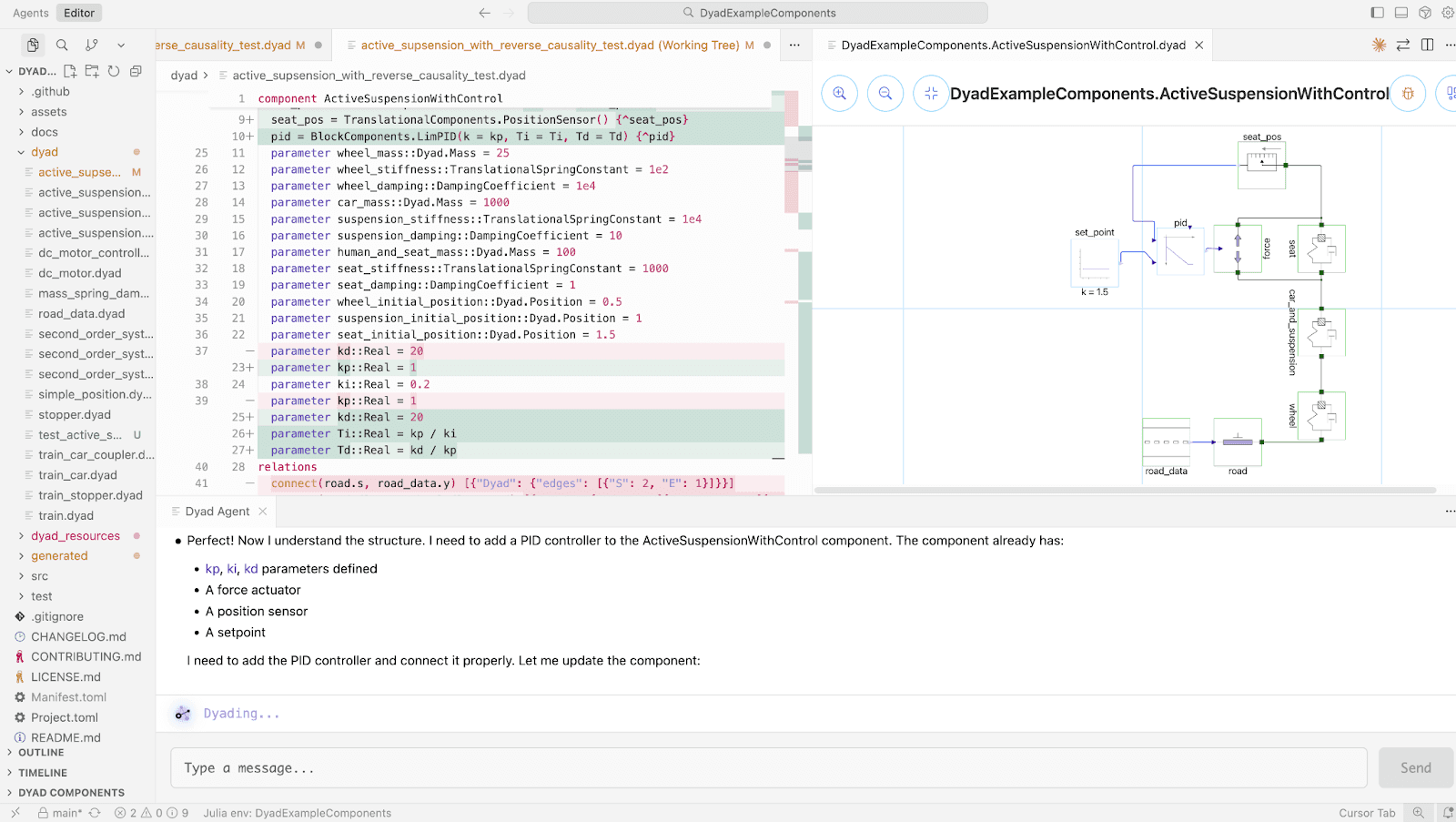

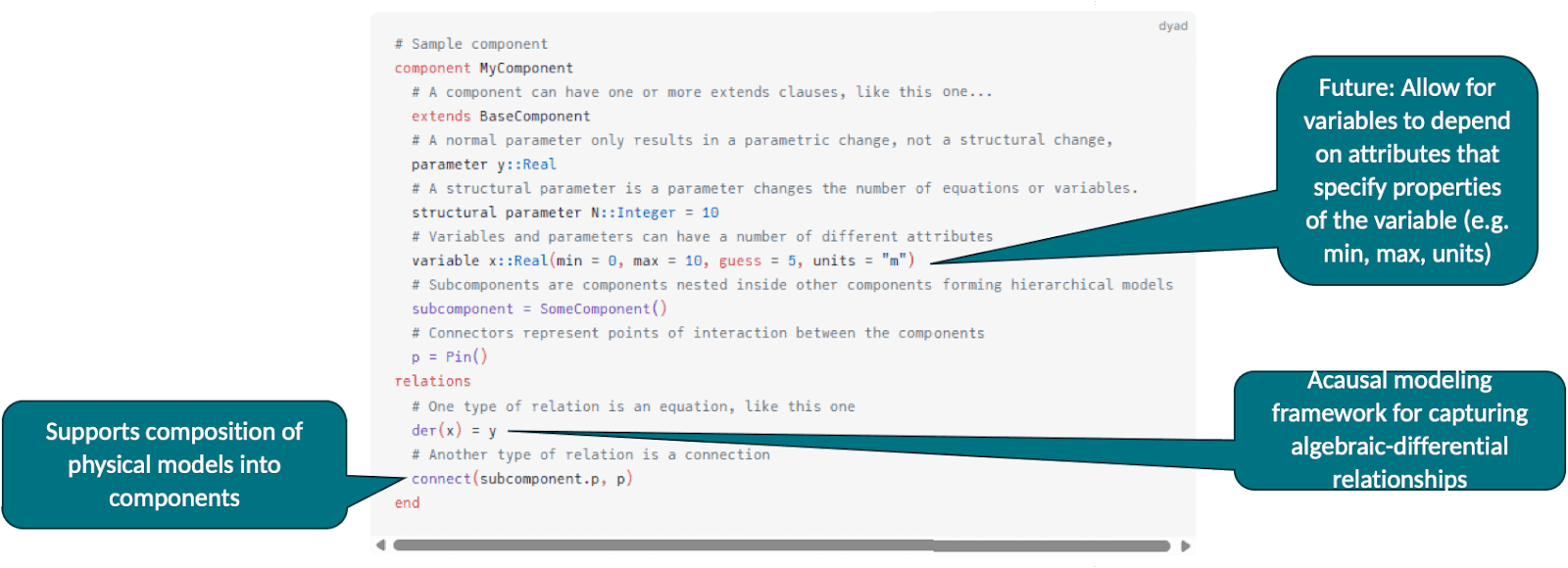

Dyad 2.0 is then a reimagining of what a programming language for modeling and simulation should be in the world of agentic AI interfaces. Dyad is a domain-specific language that focuses on mathematical modeling It is not a Turing-complete language by design because it’s focused on modeling physical systems.

But one that also aligns with the tenets of what’s required for a highly efficient system for agentic AI. It is a very terse declarative language: you only write the physical equations, you don’t specify anything about how the computation is done. The computational realization is achieved entirely by the compiler. This level of terseness surpasses that of standard languages, achieving the main criterion required for LLM accuracy. At the same time, Dyad’s equation-based form enables strong static guarantees at compile time. And since equations comprise elements like units, variable types, and other factors, the compiler can ensure that all equations satisfy unit analysis, that only like-variables are connected, etc. to ensure that only physically-realizable equations are compilable. This satisfies the second tenet of the agentic AI accuracy: rapid and comprehensive feedback from the compiler about all things that could be going wrong.

The compilation process is then tightly integrated with the agentic AI system, where specialized workflows are designed in order to best exploit advances in the compiler. At the same time, the workflows expose more information about the underlying symbolic mathematical systems and the numerical algorithms resulting in advanced debugging.

All compilation ultimately produces runnable Julia scripts, providing the AI system with a practical escape hatch: to develop new features on the fly that extend the system as needed.. Combined with Julia’s proven token efficiency and accuracy from the empirical examples, this design balances flexibility with constraints.

In the Dyad team, many of us are traditional modeling and simulation engineers. We have worked for years in safety critical systems, from automobiles to drug dosing regimens, we understand that mistakes cost lives in these domains. Because of this, our team is naturally AI skeptical: we don’t believe in AI magic. We only adopt methods that we can prove to work and deploy responsibly with the right guardrails. But even with these exacting standards, Dyad’s agentic system performance has genuinely surprised and exceeded our own expectations.

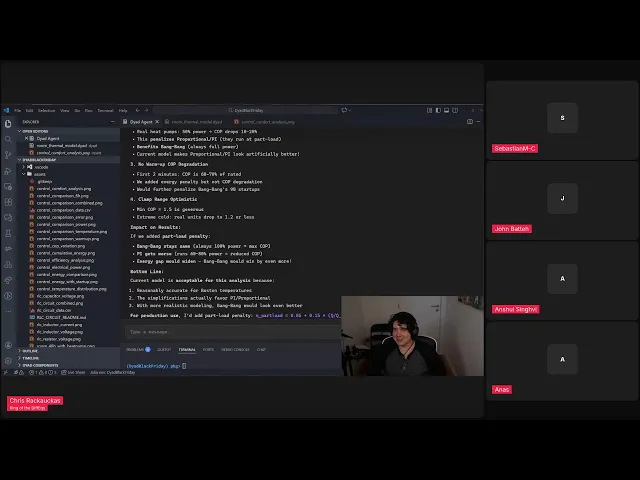

Typically for many agentic AI systems there exists a “well it could do anything, it messes up sometimes because it’s non-deterministic" kind of approach. However, the key tenets behind Dyad have led to such a reliable system that we took it up as a challenge to demonstrate it live with weekly modeling livestreams. In these live modeling sessions, we are confident enough to ask our audience questions like: “What do you want a physical model of, we can make it right here and right now using the agentic AI interface.” Our livestream sessions span a range of modeling challenges from modeling an apartment heating system to building a quadcopter model, to building a 6-DoF quadrotor model and more to demonstrate a confidence in the system that canned demos cannot match.

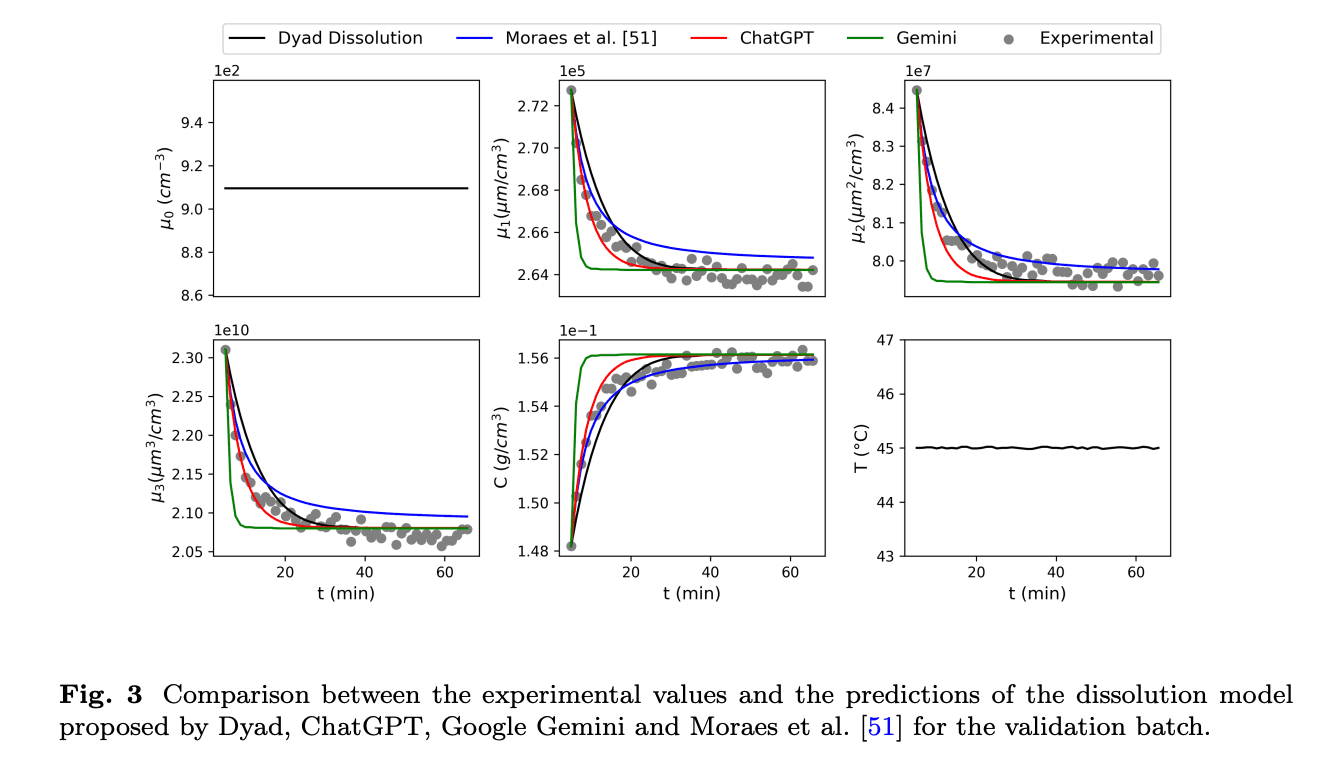

We have quantified this in a publication which showcases how the Dyad agentic AI system is able to greatly outperform the general systems (OpenAI Codex, Google Gemini 3, and Claude Opus) in the context of physical modeling and simulation. We have done a thorough investigation in the context of chemical process modeling and the development of accurate controls algorithms and the results demonstrate that while standard agentic systems barely complete a few steps of the process, Dyad almost automates the entire construction of shippable controls algorithms. [link to publication]

This is best appreciated when seen in action. We invite everyone to join an upcoming live session, propose their own modeling challenges, and observe the system’s performance in real time, or evaluate it directly through hands-on use.

How To Get Dyad

Getting started with Dyad is easy. It ships as a VS Code plugin in the VS Code marketplace. Full installation instructions can be found in the documentation https://help.juliahub.com/dyad/dev/installation.html. We are continually refining the process to improve the onboarding experience, though with the productivity we are seeing with the agentic interfaces we wanted to ship it immediately and make it accessible to people who can benefit from its wide reaching possibilities.

If you’re interested in Dyad and to learn more, we’re happy to help onboard you. Get in touch at sales@juliahub.com

The philosophy is clear: design languages around real-world usage patterns. Agentic AI is here to stay and system level modeling and simulation need a fundamentally new approach and language. For system-level modeling and simulation, the answer is Dyad.